The Myth of the Superior Hungarian Technology Vol. I. – Trains to Malaysia

This might be a somewhat difficult read for some, but it needs to be done: some of the biggest accomplishments of Hungarian industry abroad came with a heavy price – with the occasional genuine wins.

I’m starting this series knowing full well that it’s a very niche subject and most of the English speaking world is not as invested in uncovering industrial history of a small Eastern European* country as I am. Nevertheless if you indulge me I promise there’s an interesting dramatic arc to all of these stories, and maybe you can get an idea why a planned economy interacting with the open market can produce mixed results for both.

It is probably not a surprise that the Hungarian economy went through a bit of a roller-coaster ride in the 20th century: starting out as a named partner in a major European power, going through the motions changing forms of government and ruling ideology ended up by the second half with something we euphemistically refer to as “building the foundations of Communism” – even Crossrail was able to complete foundation work in less time. What resulted is an open economy that’s very much dependent on foreign export, especially to the West in exchange for the hard currency to import consumer goods and technology. Despite the forced industrialisation of the country in the 1950s, Hungary largely remained an agrarian economy – and the export of said goods were often prioritised over domestic consumption. Compounding the already existing and unaddressed pre-war poverty and scarcity as a direct consequence of two lost world wars, little wonder that the country struggled.

As it became an economic necessity to build trade relationships with the West, the Johnson administration’s decision to finally at least set aside the “Hungarian question” for the time being opened a lot of doors abroad: and at least two Hungarian heavy industry companies were able to build on their prior experience to construct and export machines, predominantly to COMECON member states – mainly the Soviet Union but we will return to that particular relationship later on – and may of the “Unaligned Nations”; one of these companies, Ganz-MÁVAG was something of a powerhouse when it came to locomotives and wagons. The company originally founded by Swiss-born Abraham Ganz, who moved to Budapest in the 1840s. At the time the Hungarian capitol was something akin to what the Gulf states were in the late 90s-early 2000s: an up-and-coming city with huge potential and wealthy backers of new ideas, such as Count István Széchenyi, the reform-minded aristocrat and politician, who after travelling extensively around Europe decided he will drag Hungary kicking and screaming into the 19th century. Ganz set up his own iron mill in 1844 in Budapest and quickly gained a reputation for insane levels of industriousness – one of the rather alarming anecdotes told about him is that he lost his eye in a casting accident and reportedly he said after the fact “Half my sight is gone, but the casting was a success!”

His tenacity and inventiveness made his company one of the largest steel mills and railway factories in Europe, until his tragic suicide in 1867. His successors continued with the ethos he represented and throughout the decades Ganz prospered and survived well into the 1950s, when it was consolidated with other companies into the state-owned industrial giant that became known as Ganz-MÁVAG. The company was one of the main suppliers of locomotives and rolling stock to the state-owned railway company MÁV (Hungarian State Railways), and was able to obtain the right to export into Eastern Bloc within the framework of COMECON (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance, the trading structure between these countries). Because how COMECON was structured, some of these deliveries were actively loss-making – these transactions were based on pre-agreed export quotas and worked in a “product-for-product” way, measured in a trading currency the “Transferable Ruble”. The main point of this system was the Soviet Union was providing raw materials and most importantly, oil at favourable rates to the Bloc in exchange for goods and equipment. Unfortunately this turned out to be an inflexible system when it came to sudden changes in macroeconomic factors such as energy costs or wages or changing demands.

Beyond the particular “market forces” that existed domestically and within the confinements of COMECON, innovation was also a difficulty: financial and material constraints made it difficult to create the necessary technologies required to evolve. In a centralised system it was sometimes increasingly difficult to wrangle resources into research and development, and as time progressed, the technological divide between East and West only increased – and attempts to at least keep up required, once again, hard currency to purchase the components, or the license to build them.

Despite all of these, some Hungarian companies have been able to successfully export their products beyond the Eastern Bloc – Ganz-MÁVAG sold train sets and locomotives to Greece, Tunisia, Egypt, and New Zealand, the latter of which operated its EM class electric multiple units until 2016. So here I’m going to leave them alone for a bit because I’m beginning to suspect that I’m losing my British readers, so to appease them enter stage left – British Rail.

British rail in the 1970s had a problem: its rolling stock especially post-Beaching were beginning to look pretty sad and old. The remaining branch lines were served by old, inadequate, and unreliable trains that everybody hated. But also it was the 1970s: a time of economic hardship and industrial strife. BR needed something quick and cheap, so they teamed up with Leyland in order to produce the solution in the form of a light train set that could serve branch lines; a rail bus.

Older British readers might get to this with sweating temples because they know what’s coming next: the dreaded Pacer. Yes, eventually the LEV (‘Leyland Experimental Vehicle’) will end up as the most permanent temporary solution in Britain, but for the time being we are just exploring the simple concept of mounting a Leyland bus body onto a high-speed freight car chassis and see what happens. The first prototypes were almost just that: a Leyland National bus body affixed to a two-axel railway car and even at that stage it was pretty obvious that this marriage was made in BL hell: the trains were noisy, underpowered, uncomfortable, and unreliable. But that didn’t stop them from refining the recipe into the Class 141 rail bus. Which was and remains one of the most hated train in Britain, and that’s a pretty crowded field.

By the early 1980s these stop-gap measure trains that were developed as a cheap substitute for… well trains became a bit of a problem: as much as British Railways embraced them into their bosom, in Margaret Thatcher’s Britain you have to show profit, so naturally Leyland was beginning to look for export opportunities. As luck would have it, South-East Asian countries at the time were actively looking to modernise and improve their own railway networks, so they took the opportunity to develop an “economy version” of the Class 141. You can only imagine how dreadful they must have been, a “no-frills” version of a rail bus that’s already designed to be very cheap. But the British industry still had a very fine reputation abroad – after all, Britain invented the railways. So this two-car experimental train set was quickly sent out to Thailand and then over to Malaysia for trials, where the British first countered their mirror image, and to their horror they found that in fact *they* were from the dark universe; they met the Ganz-MÁVAG-Ikarus 725.00

Ganz-MÁVAG and Ikarus (we will definitely return to them) came together for roughly the same reasons as Leyland and British Rail: there was a slowly increasing need for lighter trains for branch lines in Hungary, not unlike in Britain at the time. But in lieu of a specific decision and orders from the Higher Ups, Ganz-MÁVAG explored options and concepts in their own time. The project had to be cheap, fast, preferably built on parts already in inventory, and presenting decision makers with viable, working prototypes was probably the fastest way to force them into making a decisions. We are still in the early 1980s: while it is becoming increasingly obvious that the New Economic Mechanism, which was rolled out 1968 onwards is not living up to expectations.

What we colloquially referring to as ‘New Economic Mechanism’ in Hungary can and have filled entire books, so in a nutshell: in the late 1960s in order to reinvigorate the sluggish economy, the Hungarian Communist Workers Party put forward a series of reforms that gave more autonomy to certain sectors and companies to pursue their economic goals, which were allowed as long as they were able to deliver the prescribed outcomes in the Five Year Plans. While some companies, namely Rába and the world’s then-largest bus manufacturer Ikarus was able to take advantage of their newly-found semi-independence, for many sectors that wasn’t really an option and by the 1980s it was patently obvious that these reforms by in large were failures. The failure of said reforms provided ammunition for the hardliners to crack down of “liberal deviation” in many aspects of life, not just the economy. But for the healthier, larger companies like Ganz-MÁVAG or Ikarus Western exports became even more of a necessity as they found it harder to raise capital for investment or manufacturing.

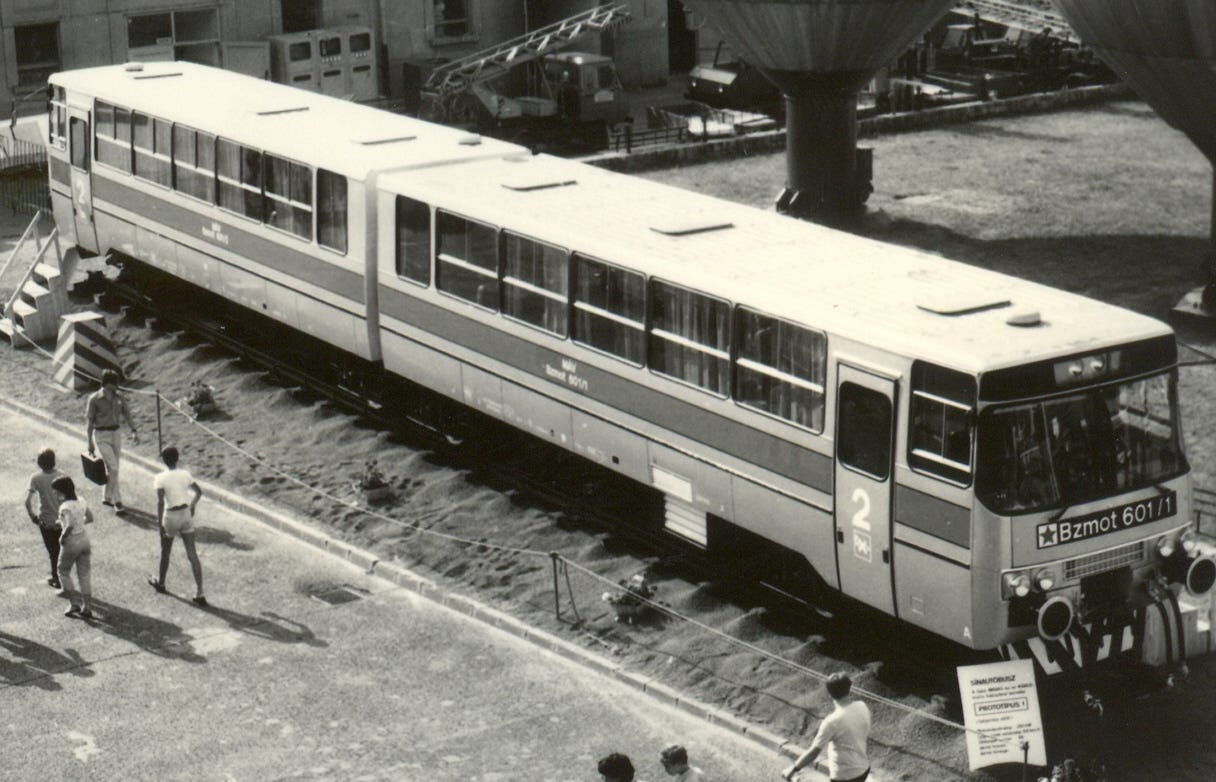

What they were banking on is not so much orders from state-owned railway company MÁV – that’s always a nice-to-have but considering that they were also in the same financial dire straits as everyone else, that seemed unlikely. Ultimately Hungarian railways decided to purchase Czechoslovak-made Bzmot Class units for branch line service, and they are still in service to this day – they were cheaper than the offering from the Ganz-MÁVAG-Ikarus group. The decision was made in 1981 for the two company to enter into a joint venture: Ikarus, a world-renowned purveyor of the finest buses money can buy would supply the body and the interior, Ganz-MÁVAG would build the chassis and the completion work. The concept was simple: Ikarus’ world-beating 200 series – which will be a subject of a future piece I promise – was designed from the ground-up to be modular: the body could be at any length the customer desired, in any seating configuration, it was an ideal light-weight construction to be used in wide variety of ways. For the prototype, which was unveiled at the Budapest International Fair in 1983, the American-made Cummins NTA 855R diesel engine was chosen – this engine was obtained through the Austrian importer, but there were future plans for utilising a domestically made engine. Having an American diesel engine served two purposes: first, it was a reliable and widely used motor, a known component thus it was the least likely to fail during tests – the Hungarian industry always struggled to develop its own domestically produced industrial engines. And second, it was proof for potential future operators abroad that they are getting a versatile and serious product for their money.

The train set was greeted with enthusiasm, and the companies were offering the two-car walk-through sets in a wide variety of gauges and trim levels. The question that’s obviously in everyone’s mind – everyone who made it this far, thank you, and actually, I’m chuffed that you didn’t bail on me this week – what is the fundamental difference between a Pacer and this Ganz-Ikarus contraption? First of all, despite the use of off-the-shelf components, some thinking went into the design. At Leyland-BREL they had the entire British rail industry at their disposal during construction: they seemingly can just put a railbus together like a LEGO set. The fact that building a passenger train on a freight chassis might be detrimental to passenger comfort almost never entered anyone’s mind: redesigning the chassis and the running gear would have cost too much money. Ganz decided to design and construct a bespoke chassis, and the Ikarus body might have had its limitation, it was infinitely more flexible to adapt than the Leyland National, because it was designed to be adaptable. As we will see, this adaptability came with a price and some serious limitations, but I’m not going to spoil it just yet – unless there is absolutely no interest in which case, thank you for staying with me, see you in the next piece that will be mercifully about movies again.

After extensive testing it was found that the train operated with high reliability and it was as comfortable as any other passenger train in service. And in 1984, following a visit from a delegation from Malaysian train company KTMB (‘Keretapi Tanah Melayu Berhad’) the train set was invited to take part in a series of tests, where the Leyland BREL was already waiting.

The Ganz-MÁVAG-Ikarus train arrived in 1985, and the contrast between the Hungarian set and the British offering became almost immediately apparent: while the “declassed” Class 141 struggled maintaining 60-70% readiness, the 720.00 was working almost flawlessly for the ten month long trials. Contemporary reports praised the train’s comfort and speed, and wasn’t for a mysterious accident shortly before the end, it would have been mostly pleasantly uneventful. Now I’m not going to suggest the British are sore losers, but leaving a lorry at a level crossing is probably a very low blow. Shortly after KTMB ordered five three-car sets and five five-car sets from the consortium, for $5 million at 1986 exchange rates, which was a substantial amount of money for a hard-currency-strapped country. The trains remained reliable and popular, but not everything was smelling of roses – as it will soon become a reoccurring theme in these pieces: there were some quality issues, and the steady supply of spare parts were also less than steady or reliable. It also didn’t help that by the time the last train sets were delivered in 1989, things inevitably started to change in Hungary.

It’s almost redundant to say that the political changes of the early 1990s hit heavy industries the hardest: thrusted from a limited but safe and predictable trading block into the wider world of free market turned out to be antithetical to what these companies were used to. They were saddled with heavy debts, decreasing orders, and the technological stagnation finally rendered them unattractive to Western buyers. In the face of unfettered international competition they were completely out of their depth and despite all the reorganisation efforts and privatisation, they slowly faded into obscurity, leaving behind abandoned brown fields. The railway manufacturing arm of Ganz was sold onto Hunslet before it finally closed shop in the mid 1990s. By that time the Malaysian trains were also out of commission. There were of course plans to modernise the concept, to improve upon what worked before but these plans didn’t progress further than a couple of nice concept drawings and the what-ifs.

Not much is known of the fate of the Ikarus 725s that run on the rails of Malaysia. Apart from a few photographs taken in the early 2000s it’s safe to assume that they no longer exist, broken apart for parts, or more likely, juts rusted in place on some forgotten siding. You might think, this isn’t a very glorious tale – on average rolling stock works for forty or fifty years before the scrap yard and some of these trains barely sailed through their seventh birthday. But I think it’s important to remember: one small country went up against a bigger country, with its centuries-old experience and capabilities, a former world empire, and won. And these are the kind of victories we, the people from small countries find solace, in the face of our overwhelming irrelevance, that one time in history, we came up on top.

Thank you for listening. Stay tuned for further stories from Hungary’s industrial history. Or not, next week it’s going to be about movies I promise.

Probably far more popular than you might think